As monsoon clouds descended over Himachal Pradesh in 2025, widespread destruction followed in their wake. Within days, landslides, flash floods and infrastructural failures ravaged the mountain state. Even as we step into August, marking the middle of the monsoon season, 170 lives have been lost, people have gone missing, and losses worth ₹1,59,981 lakh have been incurred already. While such disasters were labelled ‘natural’ in the past, they are now being termed ‘the new normal’ attributed to climate change. While the hazardprone nature of the mountains and the climate crisis are undeniably important factors, the overwhelming focus on them conceals critical issues.

In this compilation, we interrogate how infrastructural expansion, socio-ecological degradation, regulatory failure and technocratic ‘solutions’ have created compounded vulnerabilities and disaster risk in the state in recent years. We spotlight the Kullu Valley: home to the headwaters of the Beas River, and one of the most severely affected regions for three consecutive years.

When Hazards Become Disasters

Although the terms hazard and disaster are often used interchangeably, they do not mean the same thing. The IPCC and SENDAI frameworks, used to assess disasters globally, define disasters as exposure to hazard multiplied by vulnerability. With a global push for disaster governance countries like India developed the National Disaster Management legal and institutional framework in 2005. Since then, and following the establishment of the National Mission for Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystems over a decade ago, a slew of scientific reports have been produced, conducting risk and vulnerability mapping and establishing the region’s hazard susceptibility. In addition to independent studies and climate science generated from the region, the Himachal Pradesh State Disaster Management Authority (HPSDMA) has been compiling an annual Memorandum of Damages, which serves as the principal official compilation of yearly disaster impacts.

Himachal’s climate and terrain conditions place it at a high risk of multiple hazards, as illustrated in a recent study by IIT Ropar, identifying 40% of the state as high risk of hazards such as landslides, floods, and avalanches. But apart from high hazard risk, the demography and socio-economic profiles in the state significantly increase the vulnerabilities to these hazards, creating conditions that lead to widespread damages and long-term losses following hazard events.

The first map marks the very high vulnerability districts like Chamba, Kullu, Kinnaur and parts of Kangra and Shimla, considering their hazard risk and demographics. The second map indicates a strong correlation of ‘very high’ vulnerability with high-elevation zones of the Greater and Lesser Himalayas. Kangra and Una show ‘high’ vulnerability despite containing mainly low-elevation areas given their downstream location and higher exposed populations. Lahaul & Spiti is sparsely populated, and lies in the Himalayan rain shadow of the South-West Monsoon, although rising instances of avalanches and flash floods into June are indicating the growing hazard risks in the Trans-Himalayas.

The available hazard-related datasets and data trends often fall short in effective disaster management because much of this data is not standardised and granular. For instance, the absence of accurate, gridded, micro-regional rainfall and river flow data creates serious obstacles in making data-informed decisions. At the same time, more and more resources are being directed towards enhanced projections that focus primarily on the biophysical aspects of risk. This approach to disaster governance, rooted in global frameworks like SENDAI and broader climate strategies, reflects a simplistic understanding of disasters—where nature strikes, people suffer, and government institutions respond. This, in turn, leads to a techno-managerial model that prioritizes risk prediction and projection (in times of extreme uncertainty), while failing to adequately allocate resources for redress, recovery, reconstruction, and rehabilitation, affecting the overall process of building resilience. This translates to neglect of people’s vulnerabilities, their coping capacities, and their lived experience.

Losses – those that count, those that don’t

The state of Himachal Pradesh faces mounting pressure to recover the direct financial costs of these disasters, further contributing to state debt, both through increased market borrowings and loans from the centre. The direct and indirect losses arising from infrastructure rebuilding, revenue declines, and increased borrowing continue to deepen the state’s debt burden over time. As of 2025, HP has become the third most debt-stressed state in India.

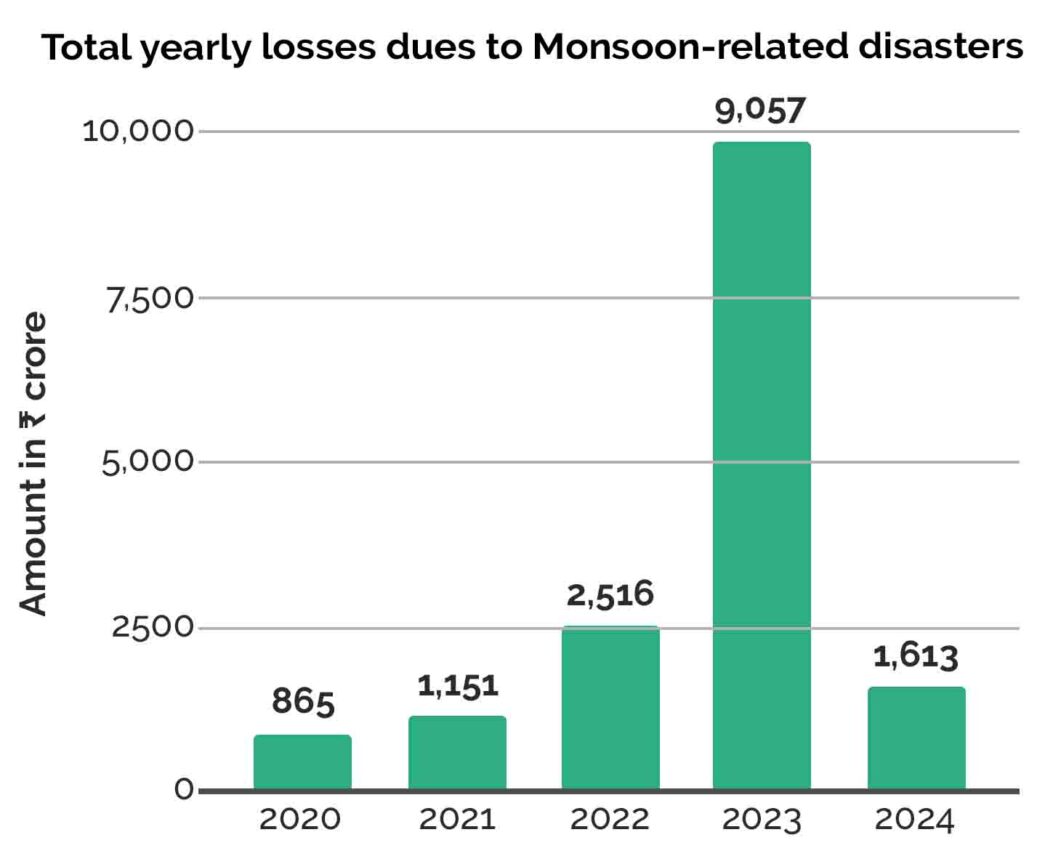

The monsoon of 2023 brought immense and unprecedented loss and damage to the mid-Himalayan region of Himachal, with over 5,000 hazard incidents recorded during spells of intense precipitation. Despite two years of lobbying the centre to release ₹9,000 crore, based on the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) conducted by the National Disaster Management Authority in 2023, the Ministry of Home Affairs released only ₹2,000 crore in June this year. The yearly losses shown in this graph are adding up to pose a serious challenge to state finances. (Data from HPSDMA Memoranda 2020–2024)

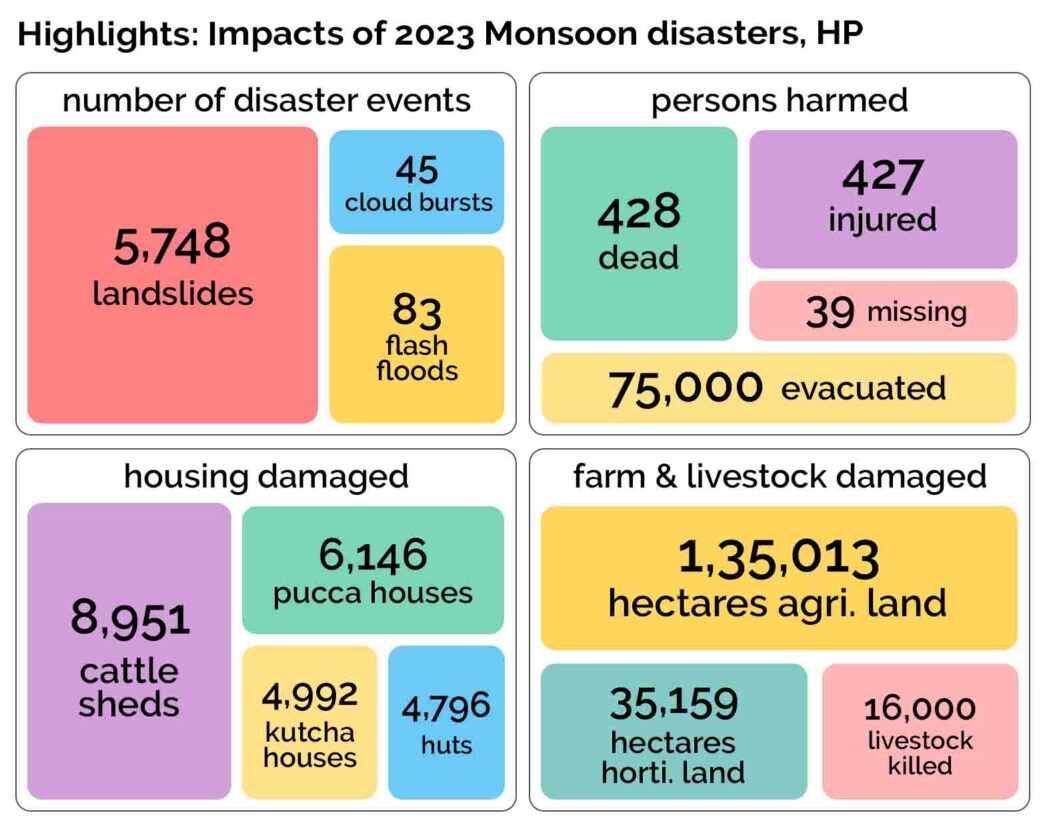

Earlier this year, after much pressure from the Kerala State Government, the 2024 Wayanad landslide disaster was declared a calamity of ‘severe’ nature, making it eligible for Central Government assistance. While the Wayanad calamity was massive in terms of the total number of casualties in a single incident (500 dead), Himachal Pradesh saw a series of extreme rainfall, landslide and flood events across multiple locations during July and August 2023, that cumulated in 428 deaths. But, as the adjacent image shows, the key data points of the overall impacts reveal a distressing bigger picture. (data from PDNA, 2023, and HPSDMA Memorandum, 2023)

The seriousness of a disaster is often determined based on the number of fatalities. However, Himalayan floods and landslide hazards typically given lower population densities, unless there is an exceptional event like the Kedarnath disaster where large numbers of tourists were affected, have fewer fatalities. Floods and erosion, while less deadly, tend to have more long-term consequences, such as disrupted access to basic social services and the loss of livelihoods. These impacts often remain invisible, as media coverage tends to sensationalize rescue operations and focus on death tolls. Moreover, national attention usually lasts only until tourists are evacuated, even as local residents continue to struggle in the aftermath for much longer. The time available for recovery between successive events is also becoming shorter now.

For a state like Himachal Pradesh, where over 90% of the population depends on agriculture, horticulture and tourism, the implications for both the local and state economy are inevitably significant. Livestock rearing, which is an integral part of the land- and forest-based economy, has also been severely affected in these disasters, as reflected in the high number of livestock deaths in 2023 assessments.

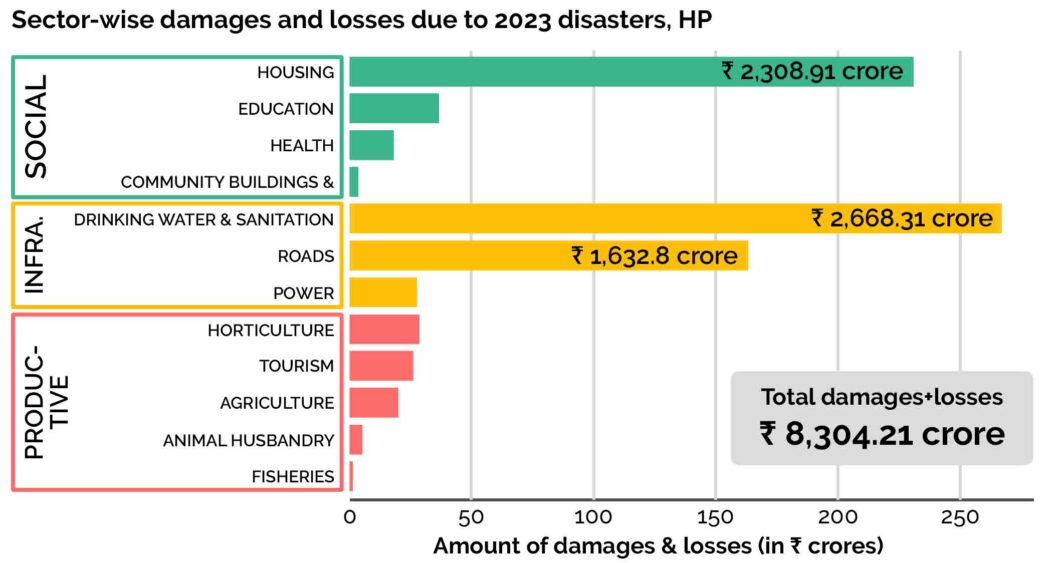

As illustrated in the graph above, the social and infrastructure sectors suffered the most damage, alongside private assets, including the complete or partial destruction of houses, watermills and cattle sheds. Given that marginal farmers make up the majority of agriculturalists in the region, they bear the brunt of these losses. Geographically isolated and socio-economically vulnerable communities take much longer to recover from personal losses (eg. loss of housing or land) and disruptions in infrastructure (education, health, water, etc.), both due to their compromised capacities as well as their low priority in administrative response.

Social and economic marginalisation not only affects the coping capacities of victims, but in some cases makes them more exposed to harzard risk itself. The PDNA report of 2023 specifically mentions that “the affected families, primarily the widows and their children, face an uphill battle in rebuilding their lives. The loss of their already limited possessions further weakens their financial stability”. While the report includes Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in the list of vulnerable groups impacted by the disaster, there is no in-depth caste-disaggregated analysis of damages or recovery.

Brunt-bearing districts

The most disturbing visuals of destruction, like landslides, mudslides, and floods sweeping away shops, buildings, cars, bridges, and roads, emerged primarily from Kullu, Mandi, Kangra (Beas Valley) and Shimla (Sutlej Valley) in the last three years. Alongside these were instances of slow land subsidence, similar to the situation in Joshimath, though they received limited coverage. These, too, were concentrated in the same regions and remain ongoing, though they have since faded from the national news.

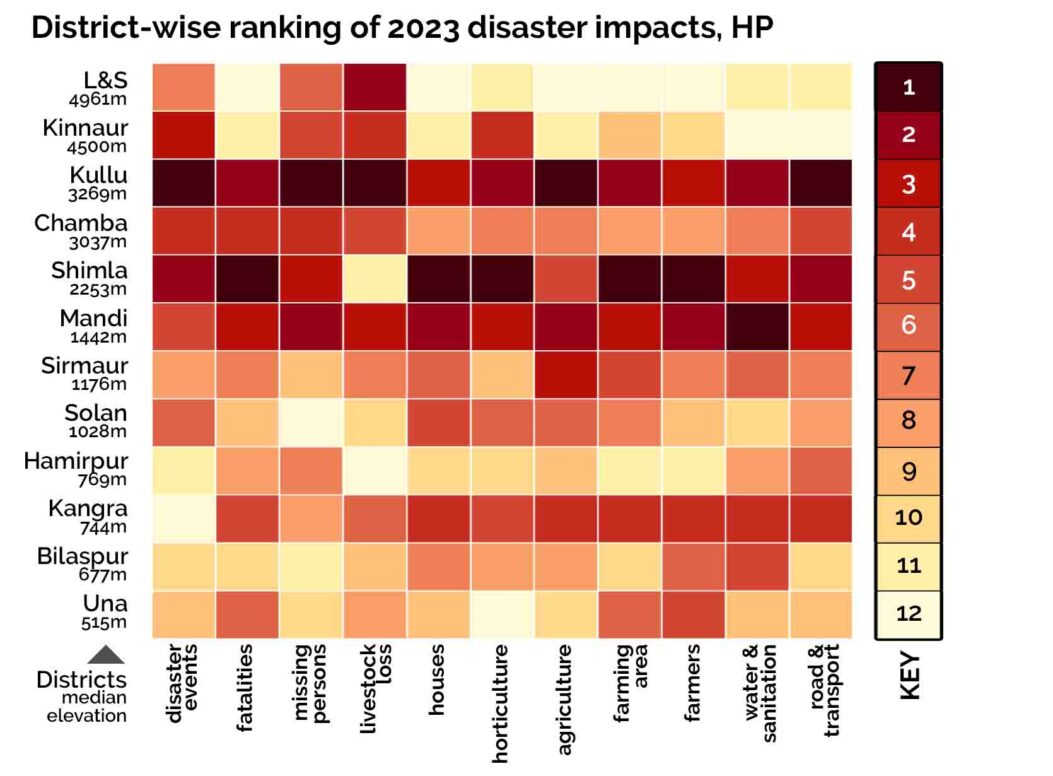

This heat map ranks HP districts based on the scale of impacts of the 2023 disasters, revealing that Kullu, Shimla and Mandi experienced the most severe losses, followed by Kangra, Chamba and Kinnaur. Kangra’s low-lying areas experienced heavy damage in floods, while the Trans-Himalayan district of Lahaul & Spiti went through 28 landslide incidents. In Shimla city, 20 people were killed in a single landslide incident on August 14, 2023. (Data from PDNA, 2023, Memorandum 2023 by HPSDMA, and Cumulative Report by Department of Revenue, HP)

To understand how the protracted and compounding nature of these monsoon disasters, we examine Kullu district, which became the epicenter during the deluge on July 8th, 9th, and 10th back in 2023. As shown in the heatmap above, Kullu suffered some of the highest material losses. The district is crucial for two reasons. First, the Parvati (including the Malana sub-basin) and Sainj valleys experienced further severe flooding in 2024 and again in 2025. Second, the upper Beas valley in which Kullu falls, exemplifies how topographical sensitivities, unregulated infrastructure expansion and the climate crisis are compounding disaster risks and vulnerabilities.

Next page Hazard-proneness of the Upper-Beas Valley