SPOTLIGHT ON KULLU VALLEY

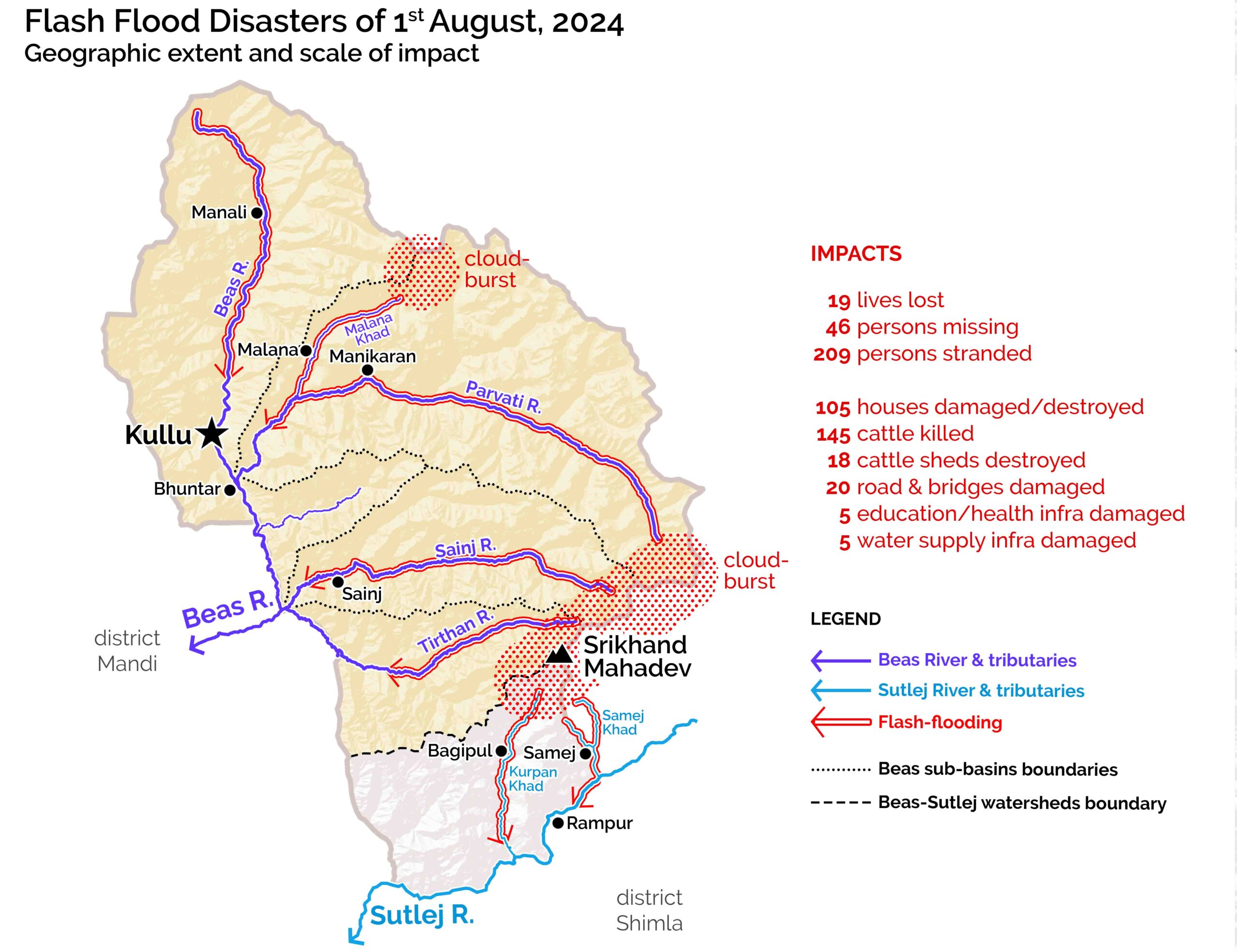

On 1st August, 2024, a cloudburst near the Srikhand Mahadev pilgrimage site triggered devastating flash floods in Samej Khad and Kurpan Khad in district Shimla, and Sainj River and Parvati River in district Kullu. Another cloudburst caused destructive flash floods in the Malana Khad, while water in the Beas River rose due to heavy rains, stranding nine people in Charuru village. The losses and damages that followed reveal the cascading and widespread impacts of a hyper-local weather event, escalating the scale and span of disaster.

The Beas River, part of the larger Indus basin, has the second-largest catchment area in Himachal Pradesh after the Sutlej, covering 13,663 km². Originating at Beas Kund near the Rohtang Pass, it flows south-west over 286 km through the districts of Kullu, Mandi and Kangra before entering the Pong Reservoir and eventually merging with the Sutlej in Punjab. In Kullu district, major left-bank tributaries of Beas, namely Parvati, Sainj and Tirthan Rivers, play a crucial role in shaping the hydrology and flood dynamics of the region. The sub-basins of these three rivers form three distinct river-valleys. The southern area drains into Sutlej River, which marks the boundary between districts Kullu and Shimla.

Hazard-proneness of the Upper-Beas River Basin

The Beas River basin is highly susceptible to hazards due to its complex geomorphic and climatic setting. Sharp altitudinal variations, intense monsoonal winds, extensive glacial and snow cover and thick forests make this region prone to flash floods, cloudbursts, avalanches and landslides. While snow avalanches occur frequently in the upper reaches, their impact is limited as these zones are largely uninhabited. In contrast, the lower slopes, characterised by rare flatlands, have become densely settled and cultivated, creating an inland topographic oasis within otherwise rugged terrain. This has significantly increased exposure to riverbank erosion and flooding.

View of Jia in Bhuntar, showing Partvati River flowing under the Jia Arch Bridge, to confluence with the Beas River. The slopes in the foreground show areas of Shamshi and Bhuntar towns. Urban development is concentrated in the lower slopes along the river. These form rapidly urbanising ribbons of intense landuse and infrastructure development including 4-lane Highways, airport and bus stands, dense housing, tourism activity and social infrastructure.

Studies from and prior to the 2023 floods show that Kullu valley is particularly vulnerable. Of the 36 recorded cloudburst events in Himachal between 1990 and 2014, 15 occurred in Kullu alone. These intense precipitation events lead to high discharge, rapid erosion, and frequent destruction of infrastructure and property. From the 18th century to 2003, historical records show a recurring pattern of flash floods in Kullu, with increasing frequency in recent decades likely linked to accelerated and unplanned development across the valley.

According to the IPCC (2014), the frequency and intensity of extreme floods are likely to rise due to the increased water-holding capacity of a warming atmosphere. If current warming trends continue, colder climatic zones are expected to shift to higher altitudes. This would accelerate glacial melt, contributing to additional runoff in humid climate regimes such as the Kullu valley. Interestingly, while major slope failures and landslides were historically limited to the periglacial zones and higher catchment areas in Kullu, the district has recently recorded a surge in landslide events, particularly during 2023–24, potentially linked to rapid land use changes and unregulated development.

Satellite imagery indicates that the Parbati Glacier, a major water source for the Beas River, has retreated by 578 metres between 1990 and 2001 – an alarming rate of nearly 52 metres per year. From 1962 to 1990, the glacier’s length reduced by 5,991 metres and its extent shrank by 8.3 square kilometres. Additional losses of 1.93 sq km (1990–1998) and 1.32 sq km (1998–2001) have also been documented. This rapid retreat is significantly higher than for many other Himalayan glaciers, largely because 96% of the Parbati Glacier lies below 5,200 metres in altitude.

Satellite data reveals that the number of glacial lakes in the Beas basin increased from 67 in 2013 to 89 in 2015, with most being small but potentially hazardous formations (Himachal Watcher, 2016). The photograph on the right shows the peak of Hanuman Tibba standing tall above the Beas Kund glacier that marks the origin of the Beas River. According to a 2014 study by G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development, this glacier is small and melting faster, posing an increasing risk for the valley downstream.

Land-Use changes in recent times

A 21-year study by scientists at the G.B. Pant National Institute revealed a dramatic 378% increase in the average occurrence of extreme weather events (EWE) between 2016 and 2020 compared to the previous 16 years in the Beas Valley. Nearly two-thirds of respondents in a socio-economic survey attributed these EWEs to noticeable shifts in climate patterns. Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) analysis further showed a massive 123% increase in agricultural land, including orchard expansion, between 2000 and 2020, alongside a 40.63% rise in settlement areas, particularly linked to tourism infrastructure such as hotels and restaurants.

The Volvo bus stand shown above was constructed along with the 4-lane road, adjacent to the Beas River. This development raises concern over unsuitable use of river-bed land, while simulataneously positioning critical infratsructure in a flood zone, increasing exposure and vulnerability to flood hazrad. This stretch is one of the many areas damaged during the Beas flash floods of June 2023.

Climatic data from the same period indicates an average temperature increase of 0.53°C, coupled with a decline in annual precipitation ranging from 76 mm to 325 mm. Despite the overall reduction in rainfall, the number of extreme rainfall days rose by 33.3%, highlighting increased climatic volatility. For the 2023 Monsoon in HP, the overall cumulative monsoon rainfall was normal with a mere 20% departure (IMD). But the rainfall during 9th and 10th July alone broke historical records in 8 districts, going as far back as 1951. It was these extreme rainfall events that triggered the high number of devastating landslides and flash floods.

These satellite images above reveal the fast urbanisation and land use shift from agriculture and forest to built-up, in village Kasol of Parvati Valley. The bulk of new construction is tourism-driven, and mainly hospitality services. The image on the right shows a cluster of hotels and restaurants that were constructed right next to the Parvati River, and were flood-impacted when the debris-carrying waters changed the river’s course in June 2023. This is another example of indiscriminate land-use change that simultaneously increases the potential of damages and losses.

Another LULC study by Negi and Irfan (2022) in upper-Kullu valley (the Kullu-Manali watershed) examined changes over two distinct periods: 1991–2005 and 2005–2020. Their findings show a decline in snow and forest cover, alongside significant increases in barren land, agricultural and horticultural areas, and built-up zones. While the first phase reflected moderate change, the post-2005 period marked rapid urbanisation and accelerated land use transformation. The increase in dense built-up occurred along the highway bordering the Beas River, and even included migration of settlements from higher slopes. Tourism, hydro-power development, 4-laning are the most significant inducers of land-use shifts in this region, and have direct implications for increasing hazard susceptibility and ecological fragility in the Beas Valley.

Next page Risky Infrastructures