SPOTLIGHT ON KULLU VALLEY

Risky Infrastructures

Kullu district, home to the headwaters of the Beas River, was historically known as Kulant Peeth, a name that evocatively translates to “the end of the habitable world”. Ironically, the popularly known Kullu-Manali is now a gateway to the trans-Himalayan borderlands like Lahaul and Leh which are new frontiers for tourists. The habitability of Kullu valley itself has been impacted by infrastructure expansion which altered land use, river flows, settlement patterns and resource distribution, triggering hazards and reproducing new risks.

Following the completion of the Bhakhra Dam in 1964 on the Sutlej River, attention turned to harnessing the waters of the Beas. Two major projects were developed: Pong and Pandoh. The Pandoh Dam, located on the border of Kullu and Mandi districts, was designed to divert 7,000 cusecs of Beas water over a 40 km stretch into the Sutlej—just upstream of the Bhakhra reservoir—marking India’s first major river interlinking project. Its primary function was to generate electricity at the Dehar Power House before discharging water into the Sutlej. This diversion left the Beas River nearly dry until it was revived near Mandi city by tributaries like the Suketi, Uhl, and Neugal rivers. This engineered alteration not only disrupted the natural flow of the river but also gradually erased the collective memory of the original floodplain, leaving communities unprepared for its revival in times of extreme rainfall.

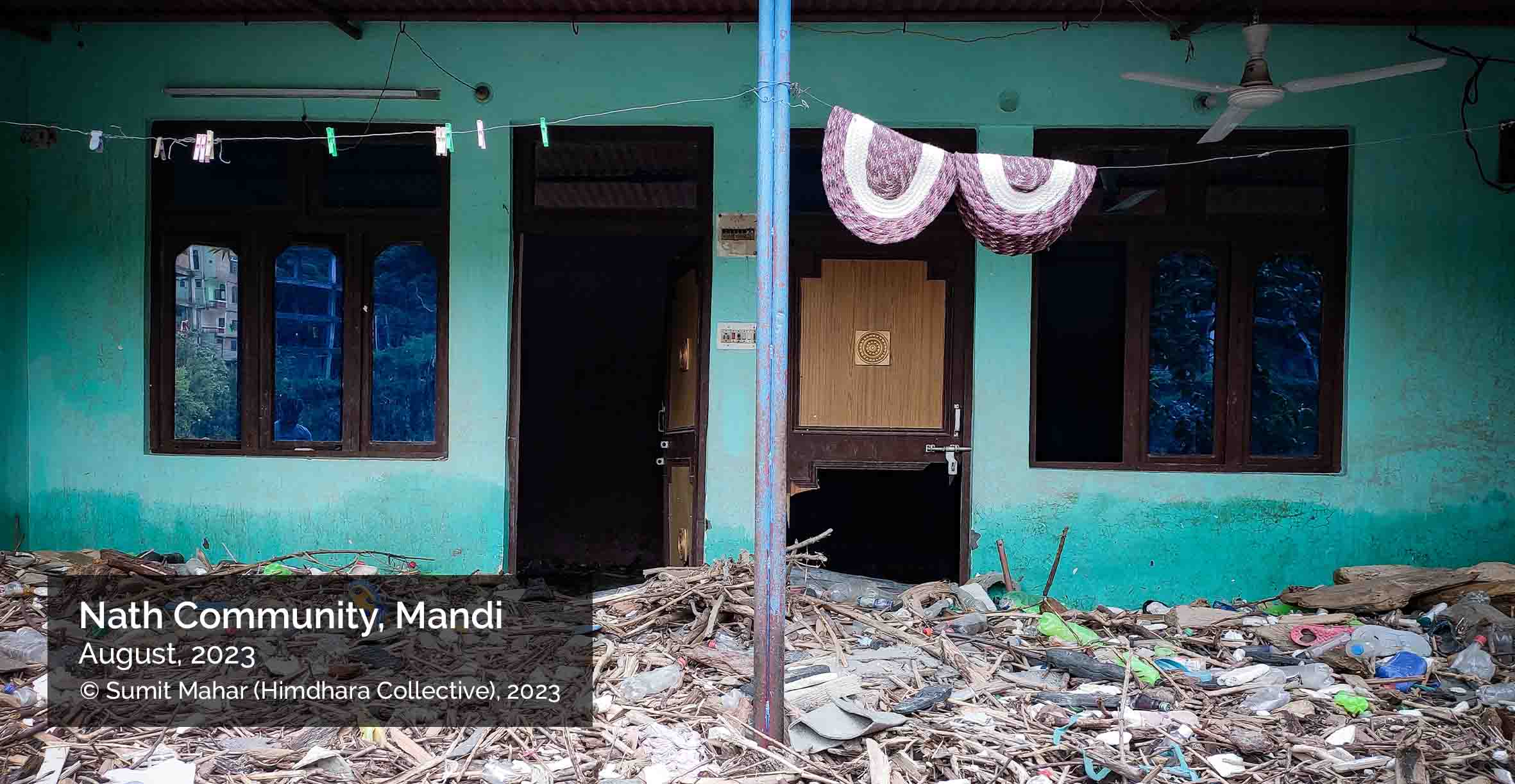

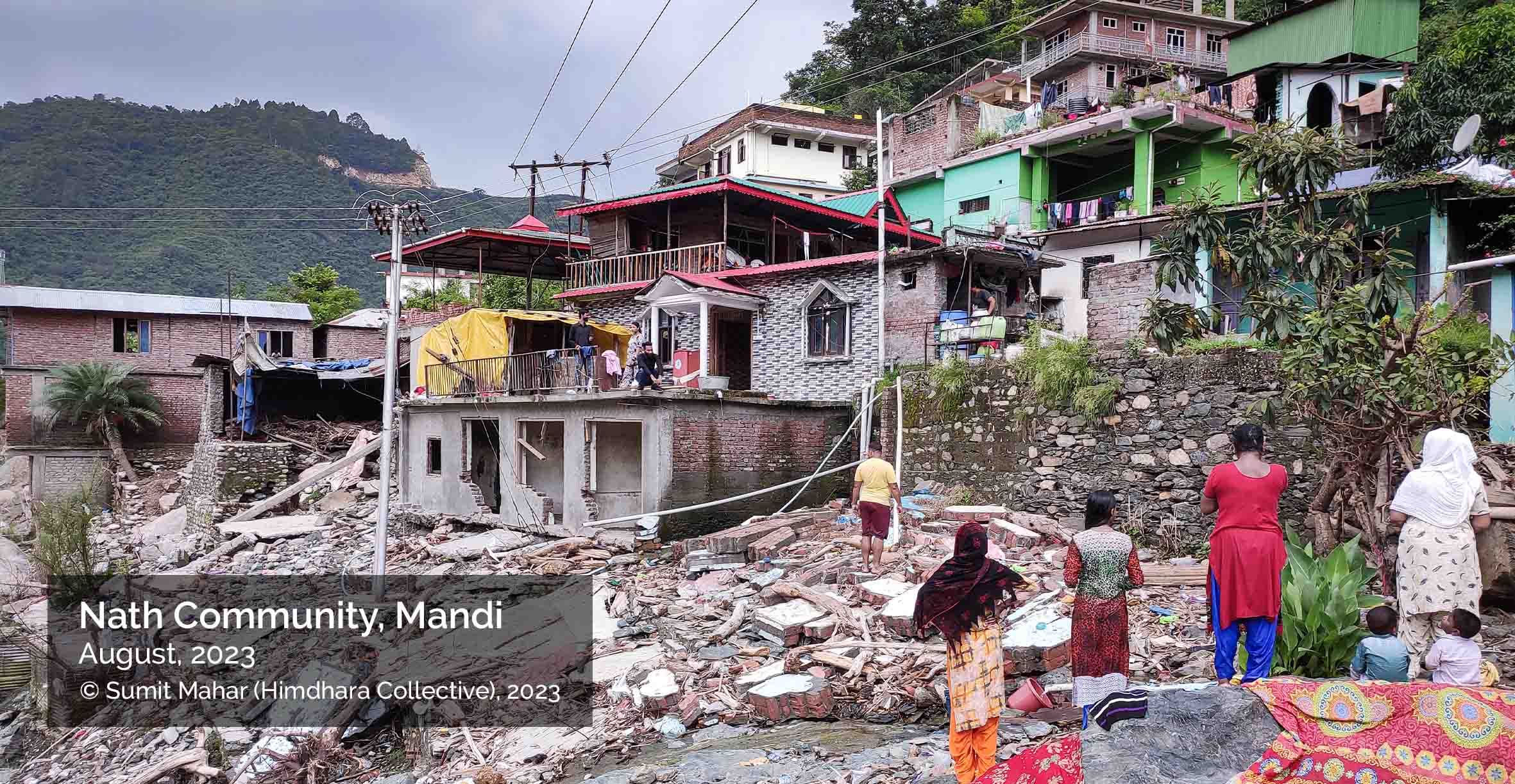

During the 2023 floods, images of a submerged temple on the Beas went viral. Less visible was the plight of the Nath community, whose makeshift homes on forest land near Mandi—allocated decades ago—were washed away. Many had worked as daily wage labourers in building the town and the Pandoh Dam itself. The photos above capture the rubble left behind.

A deluge of dams

In the post-liberalisation era, a surge of run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects has continued to fragment the Beas, visible in the map above. As of 2019, the government had identified 4,877.70 MW of power potential (>5 MW projects) across 51 hydropower projects in the basin. Of these, 22 projects are operational, 5 are under construction, 20 are under investigation, and 4 remain unallocated (CIA, Beas River Basin, 2019). The 2023 floods were exacerbated by dam water releases, with the state government later accusing hydropower operators of negligence and guideline violations (R. Negi, 2024).

A Right To Information (RTI) analysis of the Directorate of Energy’s site inspections reveals systemic lapses in dam safety management and regulatory enforcement in Himachal Pradesh. The committee constituted post-disaster documented severe operational failures at all dam sites visited. These violations include non-functional early warning systems, absence of SCADA-based gate control, lack of dam break analysis and gaps in emergency preparedness protocols (RTI file). Crucially, the committee documented that in 2023 Malana II’s gates failed due to debris blockage during a cloudburst, causing overtopping and subsequent downstream destruction. Despite repeated attempts and involvement of NDRF and technical experts, the gates remained inoperable, forcing evacuation.

In 2024, the committee revisited the site following another flood event. However, the second report failed to acknowledge or build upon the 2023 findings. It cited infrastructure losses, inaccessibility to the dam, and contradictory operational data from dam authorities. The report notably highlighted the delayed construction of a required spillway, lack of SCADA and CCTV systems, and non-functional flood forecasting. Despite recorded flood discharge increases being relatively minor, the downstream damage was disproportionately large, suggesting unaccounted vulnerabilities. Despite repeated instructions from the Directorate of Energy (DoE) and State Dam Safety bodies, crucial safety upgrades—like installing CCTV, flood marking, and automated warning systems—remained pending for over a year.

Malana I’s balancing reservoir was breached in 2024, releasing an additional 160,000 cubic meters of water, escalating downstream destruction. The report confirms structural erosion, sediment deposition and extensive damage to villages, infrastructure and farm lands. Despite these events, there was no mention of dam failure, though physical indicators suggest otherwise. Furthermore, no stakeholder consultations or mitigation actions followed the disasters and proposed meetings with affected communities were left unverified.

More concerning is the DoE’s limited punitive or preventive action. While show-cause notices were issued, no concrete accountability mechanisms were enforced and key investigative steps—such as inclusion of affected sites like Sainj and Larji—were omitted from the inquiry. Subsequent inspections failed to reference previous findings, reflecting a fragmented and non-transparent approach. This pattern reflects a broader regulatory failure where dam-induced risks are normalized and power producers are rarely held accountable, reinforcing a governance culture that overlooks cumulative ecological risk in favour of energy production targets.

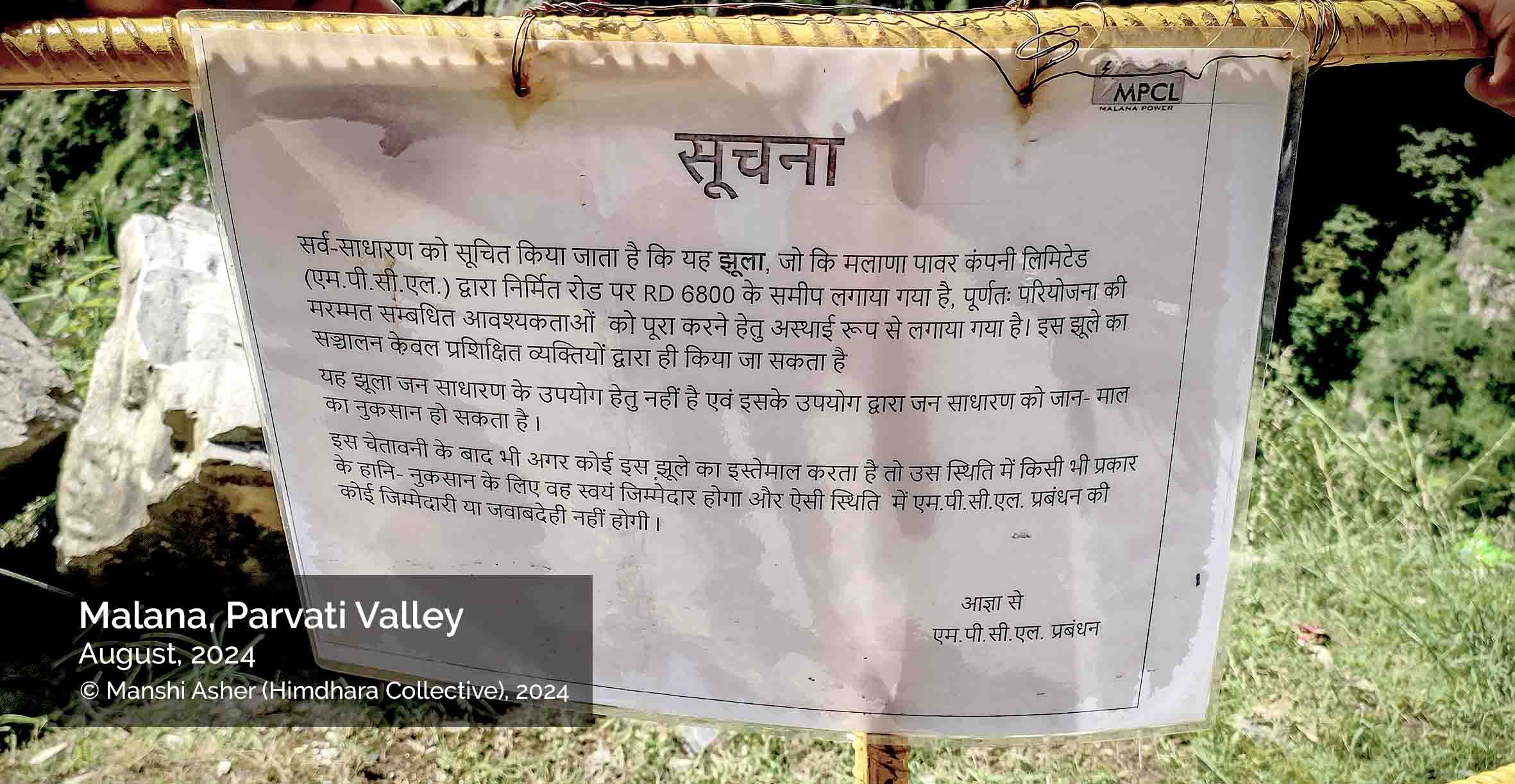

The first photo shows the bridge constructed by the MPCL. The second shows a notice in Hindi that is translated here:

Notice: It is hereby informed to the general public that this suspension bridge, constructed by Malana Power Company Limited (M.P.C.L.) near RD 6800 on the road built by M.P.C.L., has been installed temporarily to meet the maintenance requirements of the project. The operation of this bridge is permitted only by trained personnel. This bridge is not meant for public use, and its usage by the general public may pose risks to life and property. If, despite this warning, any person uses this bridge, they shall be entirely responsible for any harm or loss incurred. In such a situation, the M.P.C.L. management shall not bear any responsibility or liability. – By Order, M.P.C.L. Management

Mountains are calling

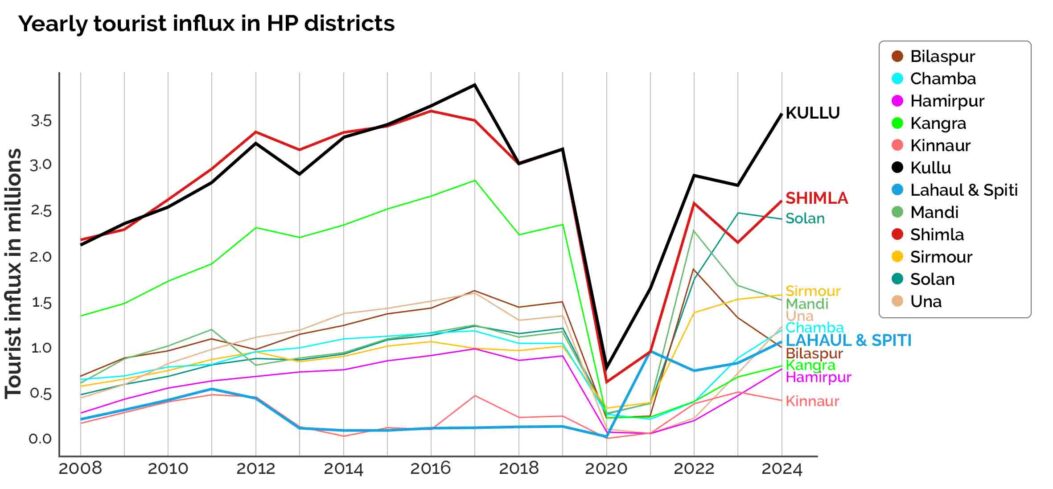

Tourism in Kullu Valley has surged dramatically over the decades—from 13,310 visitors in 1979–80 to over 67,000 in 1991–92, and further to 1.2 lakh by 1996. By 2024, the district recorded a staggering 35 lakh tourist arrivals, the highest in Himachal Pradesh, outpacing even Shimla and contributing significantly to the state’s total of 1.8 crore visitors. This surge has been especially prominent after the COVID-19 pandemic—causing the sharp dip in the year 2020—with Kullu overtaking Shimla as the winter tourism hub. The completion of the Atal Tunnel in 2020 also opened access to Lahaul and Spiti, catalysing steady tourist inflows there. Simultaneously, Solan experienced a rise in popularity, owing to its proximity to Punjab, Haryana, and the NCR.

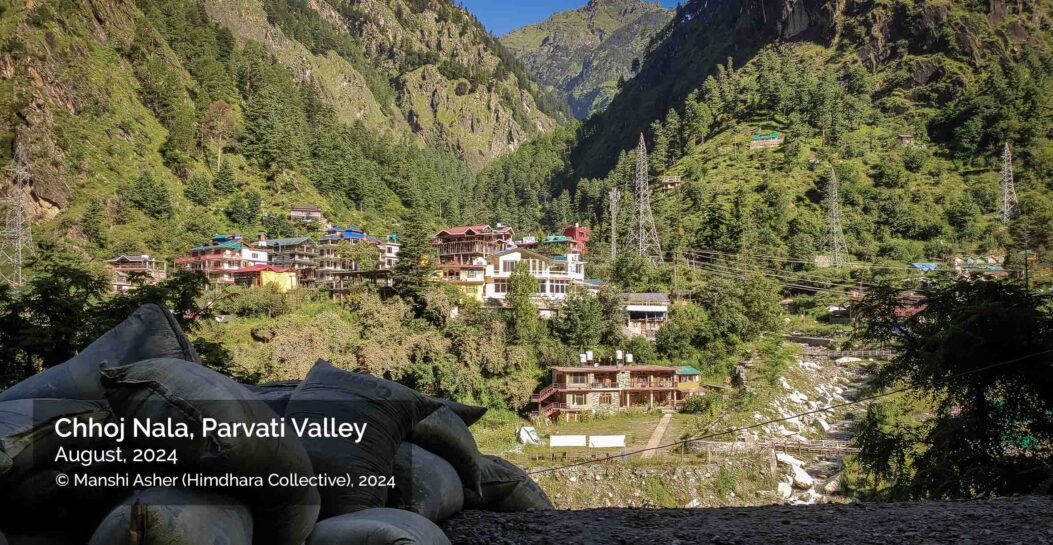

However, this exponential growth has triggered immense strain on the region’s infrastructure and ecology. In 2024, the annual tourist-to-resident ratio in district Kullu reached 6.83:1—the highest after Lahaul and Spiti. Urban centres like the Kullu-Bhuntar-Manali agglomeration now bear the brunt of seasonal tourist influxes, often witnessing daily tourist numbers that double the local population. This seasonal influx generates immense strain on infrastructure, municipal services, and land, raising serious concerns about carrying capacity. Traffic congestion, solid waste management issues and water scarcity are increasingly common while the push for tourism-centric development accelerates unregulated urbanisation and land use change.

The 2023 floods illustrated the destructive consequences of such unchecked development. Along the upper Beas River, lateral erosion intensified by hyper-concentrated flows was worsened by infrastructure, especially hotels, built directly on floodplains and ephemeral tributaries. Obstructions from suspension bridges, poorly planned public buildings and logged tree trunks temporarily blocked river flow, amplifying flood damage. Many community buildings, including schools and homes were constructed on unstable valley fills or dry channels that reactivated during the event. These compounding factors magnified the disaster’s impact.

View of Chhoj Nala near Manikaran Village, showing commercial and hospitality buildings located on the edges of the Nala and the Parvati River.

Linear infrastructures with cyclical impacts

The Beas Valley disasters over the past few years have exposed the devastating consequences of unregulated infrastructure expansion, with the Kiratpur-Manali Four-Lane Highway emerging as a key contributor. Rapid construction between Pandoh and Manali involved the diversion of over 237 hectares of forest land and 45 hectares of non-forest land with large-scale deforestation. Indiscriminate muck dumping, blocked natural drainage, raised the riverbed and reduced the Beas River’s flood-carrying capacity. Despite repeated scientific warnings, the project bypassed comprehensive environmental impact assessments by segmenting the highway into smaller stretches, evading cumulative risk analysis. The absence of floodplain zoning allowed hotels, shops, and public buildings to be constructed on unstable valley fills and ephemeral tributaries, directly in the path of high-velocity floodwaters.

Regulatory agencies failed to monitor muck disposal, while court orders against such practices went unheeded. Local communities have reported and repeatedly brought into the public eye issues around land acquisition, structural damage from blasting and denial of fair compensation. Yet, in the wake of the 2023 disaster, the Union Transport Minister dismissed these concerns, pledging reconstruction with even more tunnels, and proposing removal of shops and footpaths, further marginalising residents.

Photos of road sections damaged in Burwa and Manali due to 2024 floods in Beas, and the snow gallery—a structure over constructed to provide protection from snow and avalanches over a road section—in Solang affected by a landslide.

While the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) has received much flak over the past few years at least in the media, the role of the Border Road Organisation that built the Rohtang or Atal tunnel, has escaped scrutiny. Hailed as a high-altitude engineering marvel that connected Lahaul with Kullu district, easing local mobility for a region that faced hardships, the tunnel has also altered drainage patterns and destabilized slopes. ‘Cloudbursts’ near the tunnel’s dumping sites in 2023 and 2024 reportedly led to floods in Shanag and Palchan villages. Local residents link muck disposal and weak containment walls to the surge in floodwaters. Though the PDNA and SDMA reports underplay its role, local activists have alleged its contribution in amplifying hazards Beas basin.

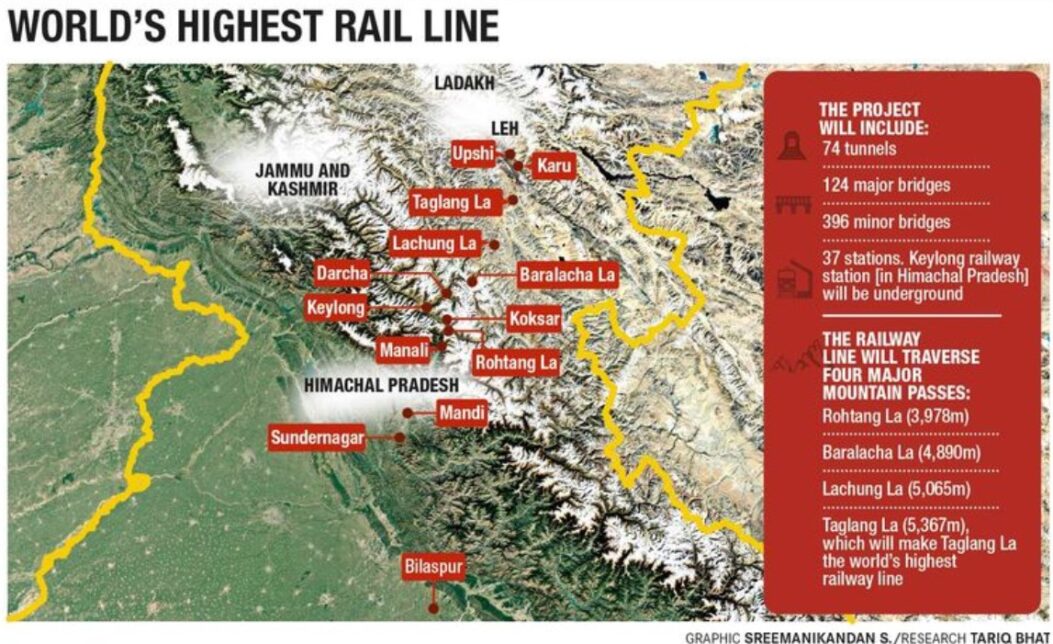

The infrastructurisation that the region is being subjected to will receive another massive boost: the 489 km Bilaspur–Manali–Leh rail corridor, the construction of which is underway. The Himachal Pradesh High Court has intervened in the Bilaspur segment of the project, issuing notices to the Ministry of Railways and the state government after residents in the district’s panchayats reported fissures allegedly caused by unscientific blasting and tunnelling work (The Tribune, 2025). The court has called for a halt on tunnelling activities, acquisition of affected land and rehabilitation for impacted families—echoing familiar patterns of ecological distress. Because both highways and railways fall in the category of ‘linear’ and ‘strategic’ infrastructures, environment and forest clearance regulations have been significantly diluted to facilitate their rapid progress in these Himalayan borderlands.

Graphic by Sreemanikandan S. Research by Tariq Bhat. Picked from “India’s costliest rail line will change how we view travel.” The Week, April 13, 2025.

Next page Questionable Solutions