SPOTLIGHT ON KULLU VALLEY

Questionable solutions: River ‘training’

It is uncontested that the annual cycle of intense monsoon rainfall, cloud bursts, flash floods and landslides have led to a surge in debris deposition along the mountain valleys, drastically altering landforms and river morphologies. The terms ‘debris’ or ‘muck’ in fact seem grossly insufficient to describe the boulder, gravel and sludge inundation which has buried farmlands, buildings and changed the course of streams and rivers in recent years. This massive volume of earth moving through the valley is not just a natural process—it’s being worsened by construction, deforestation and road-building in the mountains. In response the state approach is river training—through dredging and channelisation. In 2024 the Himachal Cabinet even made a policy decision allowing mining in private land and extending the limit on the depth of mining from one to two meters.

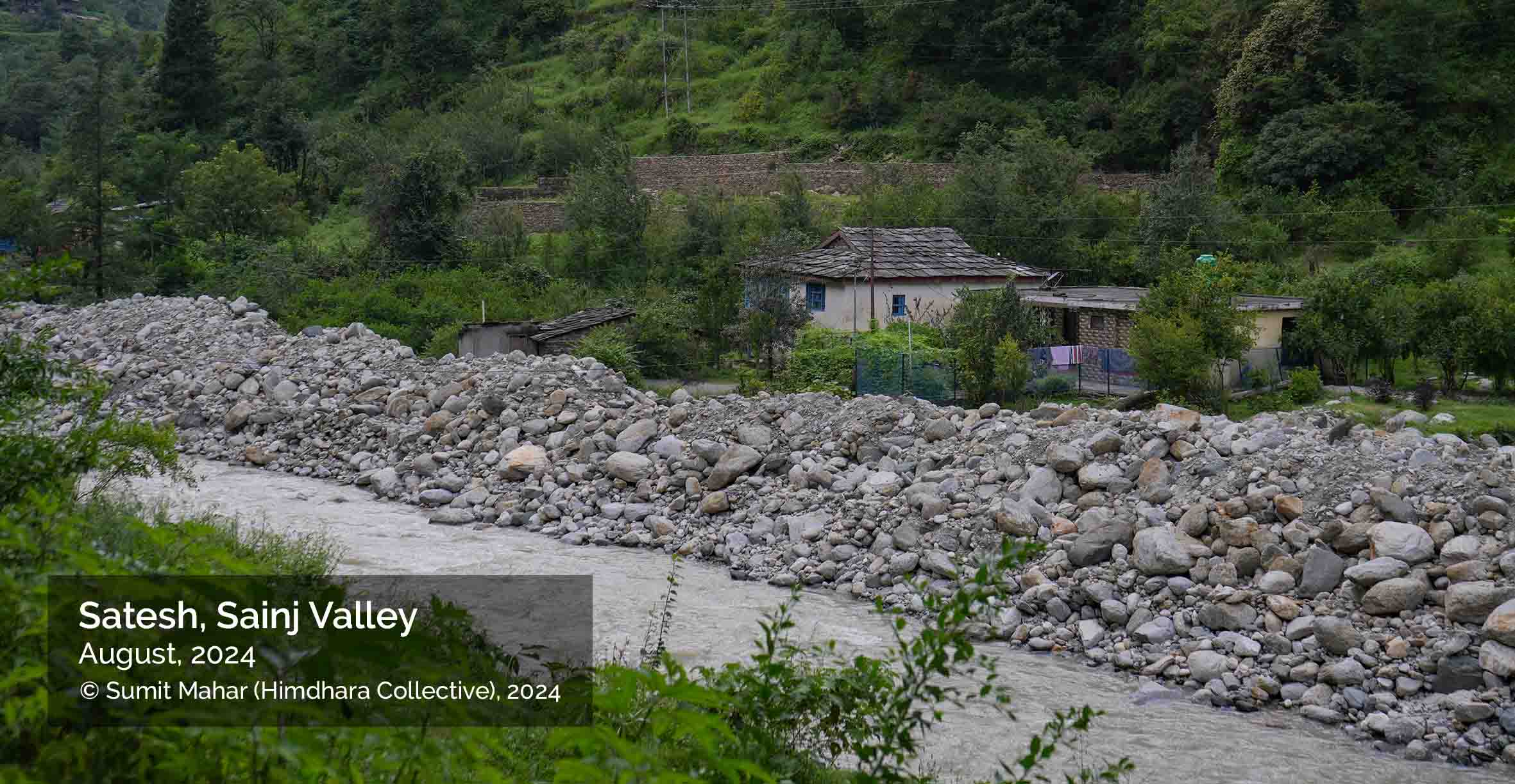

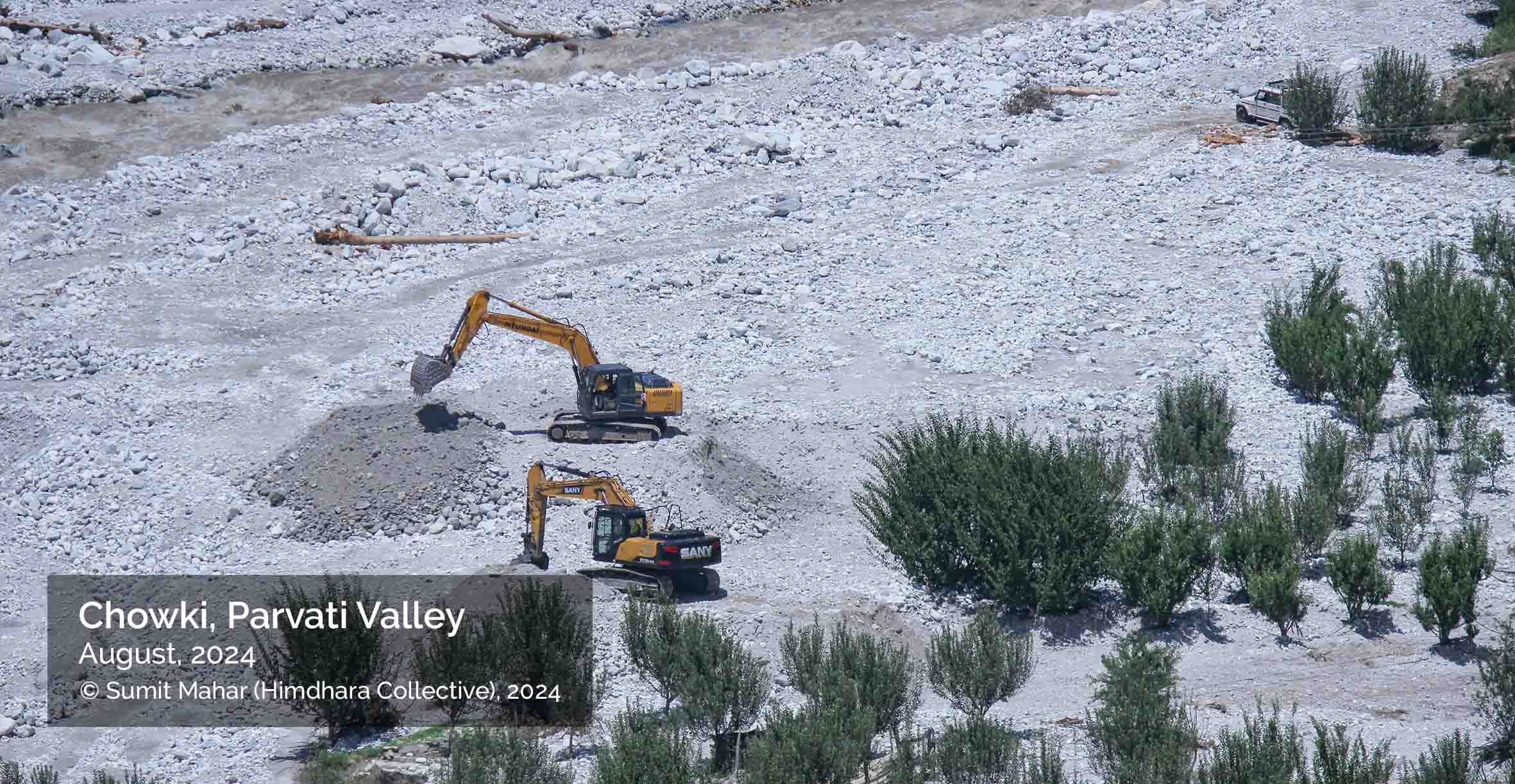

The photo above show apple orchards at Chowki village covered in sediment after 2024 flooding in the Malana Nala that has transformed the landscape drastically. The next photo shows silt debris piled along the Sainj River near Satesh.

To regulate riverbed and minor mineral mining every district is carrying out scientific assessments, and according to Kullu’s survey report the annual sediment desposition in the district is nearly 20 million metric tons—enough to bury 200 cricket stadiums under five meters of silt, or fill 8,000 Olympic pools. However, the report falls short in addressing the cumulative ecological and disaster risks arising from infrastructure-driven extraction, especially post-2023 floods. While acknowledging sediment accumulation due to extreme weather and glacial activity, it frames mineral deposits from floods—particularly in the Beas valley—as opportunities for commercial extraction rather than red flags of environmental instability. Despite detailing replenishment rates and No Mining Zones, the DSR lacks a precautionary approach to floodplains and fails to integrate lessons from dam-related disasters. It implicitly endorses mining in geologically sensitive and tourism-heavy zones without critically assessing human vulnerability.

This map plots the locations of hydro-electric projects alongside officially identified dredging sites in the district. The dredging sites are points in the riverbed where large quantities of sediment and debris have accumulated and pose flood risk at those points and downstream. Many of these sites lie downstream from large projects and official-unofficial muck-dumping sites.

Post the 2023 floods the judiciary, particularly the Himachal Pradesh High Court (CWPIL 27/2019), pushed state agencies and PWD to act on technical compliance—fixing roads, dredging rivers—without interrogating the source of sedimentation, such as unchecked construction, as required by an National Green Tribunal order. As this information provided under the RTI Act to a local watchdog—Himalayan Advocacy Centre—shows, the judiciary did not question whether dredging and river training themselves might exacerbate ecological harm especially given the fact that the locals in Raisen and Sainj valleys had raised the issue of unscientific dredging.

The role of NHAI, as evident in the court records, was limited to fund release and requests for dredging to protect highway infrastructure. However, NHAI neither conducted its own sediment impact studies nor coordinated proactively with local bodies or river basin authorities. This techno-bureaucratic siloing highlights how infrastructure protection is prioritised by the state over restoration, building community resilience or rehabilitation. The Ministry of Water Resources and the Central Water Commission (CWC) themselves have acknowledged that river dredging is not an effective long-term solution for flood control, citing the Brahmaputra in Assam as an example where siltation is too vast and recurring to manage through dredging alone.

The Himachal government was not the first to push river training post floods. The Uttarakhand government’s use of the disaster management framework to enable aggressive riverbed mining and dredging came in for criticism as an instance of leveraging crises for development gains—’aapda mein avsar‘. Under its River Training Policy launched in late 2020, district administrations auctioned rights to excavate sand, gravel, and boulders from riverbeds—ostensibly to prevent erosion—with contractors required to be the highest bidders even though such excavation amounted to commercial mining without environmental clearances. These tenders, issued under the guise of disaster preparedness, bypassed environmental regulations, leading to unchecked extraction with no safety protocols.

Additionally, a proposal for channelisation to tame the ‘snaking and unruly’ Beas River has also been submitted to the CWC. The proposal which was returned back to the state government last year is yet again rooted in the engineering mindset, where channelisation, typically involving concreting, embanking, or straightening river channels, is seen as a method to control flow, reduce lateral spread and protect infrastructure. Environmentalists and river scientists have provided ample evidence highlighting that channelisation leads to loss of floodplains, disrupts groundwater recharge, destroys riparian habitats and increases flow velocity, which in turn causes greater downstream erosion and flash flood intensity, only shifting the risk elsewhere, especially in a para-glacial river like the Beas with heavy sediment loads.

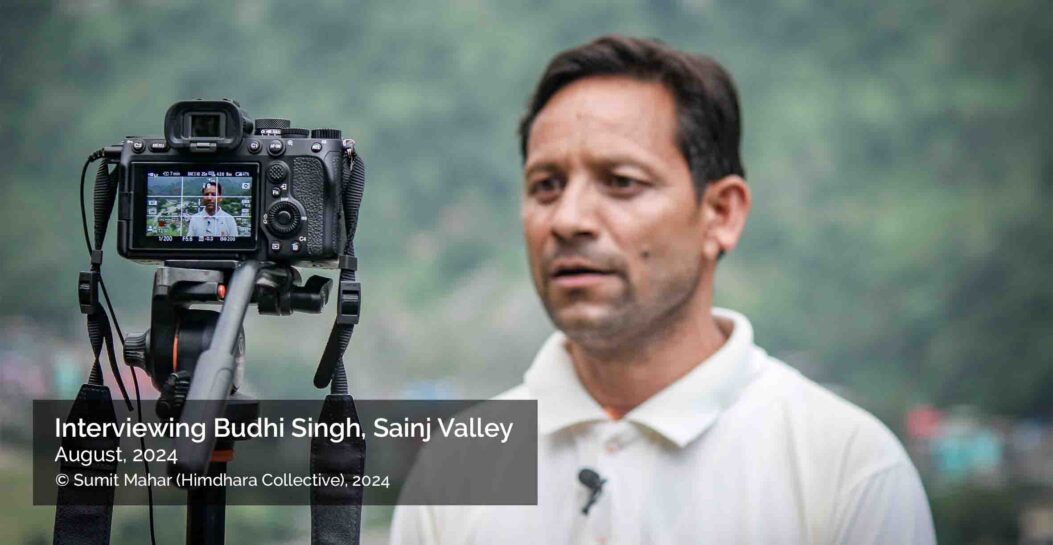

Tabahinama: Echoes in the aftermath

About two weeks after the 2024 floods we visited two severely affected sub-valleys of Kullu, Sainj and Malana (Parvati) to document local testimonies and collect visuals of the flood impacts. People’s narratives revealed the uneven geographies of risk and disaster and how communities, despite the state’s disaster governance paraphernalia, emerge as first responders engaging in rescue, relief and rebuilding. For the disaster impacted residents of the valley, and in fact many other parts of the state, the question of getting life and livelihoods ‘back on track’ looms large among other unexplainable and trying realities. The demand for resettlement and rehabilitation—away from the flood impacted zones rendered unsafe—is now gaining public momentum in another year of disasters and has been acknowledged by the state government. However, it is the central government that needs to intervene given the non-availability of revenue land in the state whose geography is largely classified as forest, and thus subject to the provisions of the Forest Conservation Act, 1980.

While dam operations need to be strictly monitored with punitive actions as per the Dam Safety Act provisions, it is further mega-infrastructure construction that needs to come to a halt. As the lines between short, medium and long term responses blur in these cycle of disasters, negligence and absence of accountability in governance tend to recede in the background. As those who profess to love the mountains, the least we can do is bear witness, remember these catastrophes and make them part of our collective consciousness—to guide our future actions and decisions as citizens.

Our documentary—Himachal ka Tabaahinama (see below)—is a collection of testimonies of the flood-impacted locals from the two sub-valleys, published as an attempt to commit their reality to our collective memory. This 20-minute film seeks to convey the profound impact of recurring disasters on the communites trapped in their path—where stories of courage, resilience, loss and the long road to recovery are carried by those least heard and left behind:

CREDITS

Writing: Manshi Asher

Visualizations: Prateek Draik

Photographs: Sumit Mahar and Manshi Asher